Advertisements tell us that our houses need more insulation while at the same time the New Zealand Standards and Building Code has increased its insulation requirements (and will probably continue to do so). Can we conclude from this that 100% insulation is the best result? Obviously not, because a building with a 100% insulated exterior skin is often referred to as a 'cold room' or refrigerator.

With glazing, a double unit is better than a single sheet window pane, and triple glazed units will give further improvement, as will using a timber frame rather than a standard aluminium frame. Yet remember that if we grow tomatoes during the cold part of the year in a building with an exterior surface of 100% single glass in a simple aluminium frame it is called a ‘hot house’.

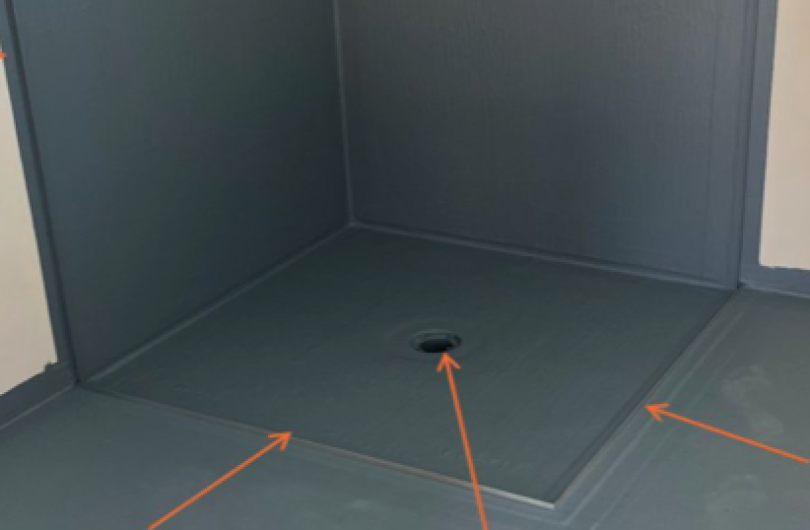

Thermal mass can smooth the daily hot/cold cycle within a home. Having more available mass is good as it prolongs the passive solar gains into the evening while if there is very little thermal storage in the building fabric then in winter, it's necessary to wear more clothing as soon as the sun goes down. By this logic, 100% thermal mass is the best, yet this is also not the answer.

These three factors – insulation, glazing and thermal mass – have a complex, multivariable interrelationship where if two are adjusted, the third will be affected. The sweet spot is where the proportions of all three come together for a unique best fit. This best fit is not only dependant on the proportions across the building fabric and the relative locations of each within the building, but also on the orientation, site contours, shading from adjacent features, climate patterns and exposure, and so on.

The problem is how to get near to the sweet spot. In the past, designers relied on simple principles and their experience and observation – with assistance from the publication Sunshine and Shade in Australasia – for the passive solar design aspects of their homes. As with structural design where sophisticated engineering software can quickly and easily explore the implications and potentials of the designer’s ideas, today passive thermal design consultants are using sophisticated thermal simulation software such as AccuRateNZ. After entering the building description, the software can produce an objective analysis of the various planning, material and aesthetic options generated by the designer. While the software does not identify the sweet spot (as with engineering it only passively analyses the given data), instead the analysis allows the three functions to be quickly manipulated by the designer to give comparative results that are ‘sweeter’ than the intuitive process.

In my opinion, while it is desirable to produce the best passive thermal design, this should not be at the expense of buildability, liveability and aesthetics; after all you can put on or take off a jersey to moderate the thermal environment but it is difficult to continually adjust the physical building.

In subsequent blogs I will expand on my views of the influence of each aspect of insulation, glazing and thermal mass on a building’s design and performance. If you have any insights to share, please feel free to post a comment below.

Most Popular

Most Popular Popular Products

Popular Products