Architects Patterson project associate Andrew Mitchell says the extensive use of glass came about by an unforeseen restriction.

"The site sits in the path of possible lava flow, so we were unable to include basement carparking," he says. "Instead, we used a spiral ramp that weaves its way through the centre of the building to balance out carparking and habitual space."

"The façade of glass is an interpretation of that parking ramp — it's three dimensional and pushes in and pulls out just as the ramp does."

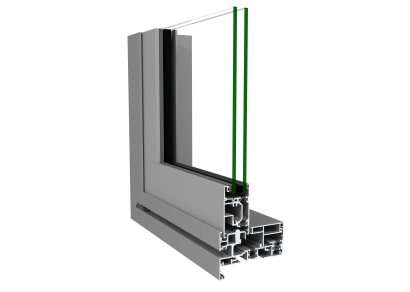

Design and manufacture challenges were aplenty in such a project, but adding to the complexity was the fact that no two panes of glass were the same. Every panel, and its corresponding joinery, was unique in terms of shape, size and angle.

So it's no surprise that joiners Miller Design and glaziers Viridian won the WANZ (Window Association of NZ) Best Use of Glass award in 2010 for their work on the Anvil project â so named for its likeness to the Anvil cloud, a dark, swirling cloud formation that appears before a thunderstorm.

"This building is unlike any other in terms of the angularity of its façade and glazed surfaces," says Mike Lewis, project manager from Miller Design. "The façade was designed for architectural impact but very little is level, plumb or linear."

Miller Design sub-contracted the glass component to Viridian. Mike says the appeal of Viridian was more than just its superior product, but because it's a local company with staff on-hand to attend design meetings and be onsite for quality control.

"They sat in on architectural meetings and their recommendations were followed — they were good recommendations," he says.

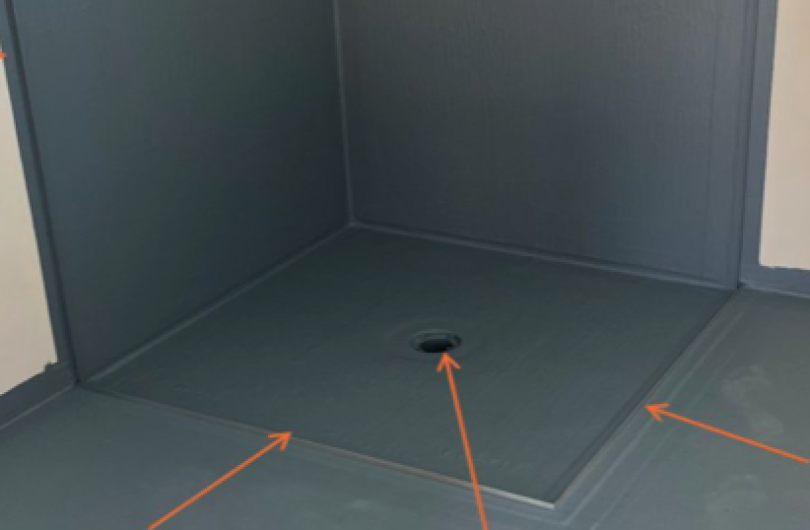

Because Viridian manufactures its own glass it was able to handle the project's specific design requirements. Low E glass was used throughout to help regulate temperatures inside, but also to deflect heat from outside. Additionally, the panels feature Viridian's Seraphic fritting, which is fired into the glass through a screen printing process. It absorbs sunlight and helps prevent heat transfer, but still allows a view out.

This inked pattern alters around the building. Lower retail levels required clear glass for shop windows and therefore fritting features only along the top and bottom of the panels. In other areas the fritting is graduated to different degrees, depending on its elevation and direction.

"Without it, the project would not have worked environmentally," says Andrew Mitchell. "The occupants would have fried with too much solar gain, and experienced too much glare on their work surfaces and in their offices."

Andrew Hamilton of Viridian says to complete the project accurately, every glass panel had to be individually designed and manufactured.

"The architects did a plan for every panel that showed where the fritting started and finished and its graduations, then sent it to the fabricator," he says. "Logistics were a critical component of this project."

Factory ready sheets of glass, some up to three and a half metres in length, were then installed into their matching joinery and hoisted into place via a crane.

"Glass did break," says Mike. "It was unavoidable with a project like this. But because Viridian is local they were able to replace it quickly. Their attention to detail and ability to respond made them the right choice for this project.

"In fact one of the best things about this project was working with Viridian. Their field supervisor was one of the best glass guys Iâve ever worked with, and Iâve worked on projects like this internationally."

New Products

New Products

Popular Products from Viridian Glass

Popular Products from Viridian Glass

Most Popular

Most Popular

Popular Blog Posts

Popular Blog Posts