John, a homeowner customer called me the other day to say he was planning to build a new home, and after doing a bit of reading about building products, he had decided that he wanted to build a ‘breathable’ home. He had also been talking to someone else about making his building airtight, and was calling to ask me which one he should go for: ‘Breathable’ or ‘Airtight’?

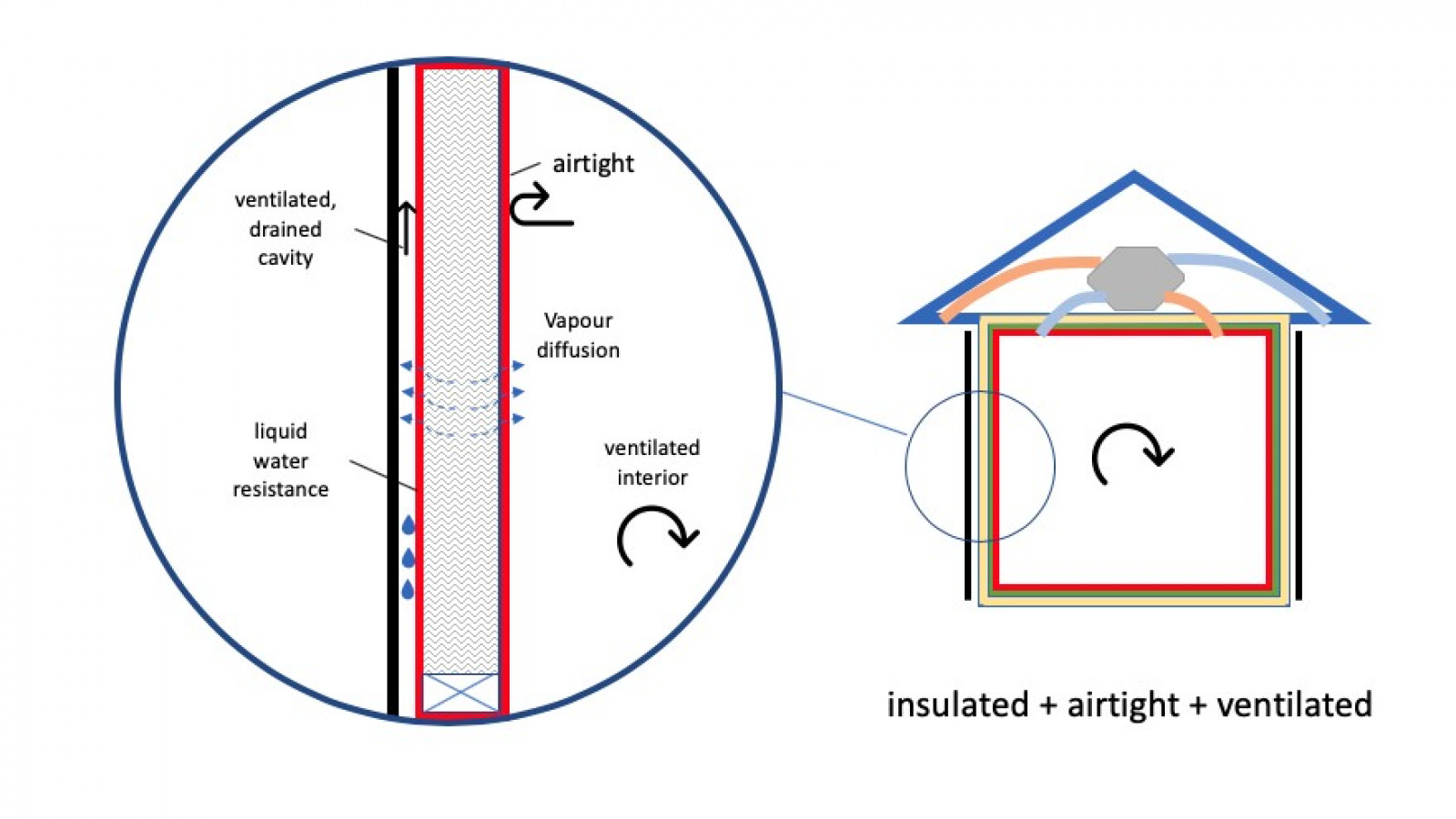

The short answer is that John can have both, or should have both if he is building a timber framed house with fibrous insulation (like the majority of houses are).

In NZ the term ‘breathable’ is commonly used (even if technically incorrect) to describe a building material or system that is vapour permeable or vapour open; in other words, a material that allows the construction to dry by letting any retained moisture escape in the form of vapour (the gaseous form of moisture). It's not technically ‘breathing’ they are trying to describe though, but more ‘transpiring’ as it often doesn't involve air movement in and out. As a building consultant once said: "If you're in something that's breathing, get out fast, as you've been eaten alive!" So yes, we do need to build our homes to be ‘breathable’ or ‘vapour open’ so moisture is not trapped in the structure and they can be free from moisture problems such as mould growth and rot.

Airtightness on the other hand, refers to controlling air movement in and out of gaps and cracks in our thermal envelope, which includes our floors, walls and ceilings (or systematic draught stopping). Insulation is basically the trapping of air molecules, so if we are allowing air movement through our insulation (from outside or inside), then we won’t be getting anywhere near the expected R value required in our thermal envelope to ensure the inside temperature of our homes can be kept at a comfortable level. A good example of trapped air being a good insulator is if we are outside on a windy day and are wearing a jersey, we might still feel cold, but if we put a wind-breaker over top of the jersey, the air around the jersey is trapped or still, so suddenly we feel warm as we are better insulated (the wind-breaker itself is only thin so has minimal R value itself, but allows the jersey underneath to work properly).

There are some building materials that are both airtight and vapour permeable, like most good quality wall underlays. And just to confuse you, a material isn't always vapour tight if it is airtight (like a good quality building underlay), but usually a vapour tight material will be airtight by nature (i.e. vapour barriers such as foil, steel or glass).

The thermal envelope of a building should have similar properties to the human body. Our skin is both airtight and watertight from the outside, but vapour permeable as we sweat or ‘transpire’ moisture out if things get a bit humid. Our skin, and our insulating fat layers are also continuous around our body, to ensure they work effectively everywhere and all the time (that's another whole discussion for a later date). Coupled with this is the super efficient ventilation system you are using right now, breathing fresh air in, and extracting carbon dioxide out as you exhale.

Just think, for you to “breathe” what we are talking about is transferring air in and out of your dedicated opening (mouth). The last thing you want is to try to “breathe” through holes in your lungs (ventilation casing), chest (building envelope) or trachea (ductwork) as then you are in real trouble.

Like our lungs and mouth, a dedicated ventilation system plays a key role in making a vapour permeable and airtight buildings function correctly, as it extracts moisture through dedicated pipes and openings, instead of any old gap or crack in our walls, floors and ceilings.

So if John (or anyone else!) builds with air-tightness, vapour permeability and good ventilation in mind, they are well on the way to having a home which is healthy and comfortable to live in, as well as being energy efficient and durable for years to come.

Most Popular

Most Popular Popular Products

Popular Products