The 2015 Paris Climate Conference was different from past gatherings in that the agenda took a radically different approach which did much to ensure its success. Instead of using the normal process of having the negotiating delegates work up the bones of a probably acceptable agreement, and then having the Heads of State come in at the end for the final negotiating and acceptance, this time the order was reversed. The Heads of State gathered at the beginning and agreed on a general brief for the working delegates to follow, so that there was no need for 'second-guessing' what might be acceptable to the various (often conflicting) interests of the leaders at the final negotiations. Equally, the leaders were not making any commitments to any particular standpoints — they were just compiling a brief. The negotiators had definite paths they could confidently follow, and the leaders could not be responsible for details which had not yet been negotiated, and anyway, they had the power of veto at the conclusion. A very neat and clever process for negotiations of such importance as these.

Apart from the obligatory horse-trading over the final words, much to the surprise of many, the conference did reach a conclusion and achieved a lot more than was anticipated. There has been criticism that commitments to specific quantified targets of timing and size of emissions were not included, just the goals of 1.5°C and 2.0°C. In my opinion, this is not a problem as the 'fuzziness' of the outcome has allowed the politicians plenty of wriggle-room which the electorate can work with over time. I am cynical enough to know that the 1.5°C will be exceeded, and that it is too late to keep back from the 2.0°C goal. By the politicians readily agreeing to aspirational goals, these are still alive even when passed so that the electorate can demand that they be returned to, whereas when fixed specific targets are missed, they are past history and usually new higher fixed targets are negotiated. The politicians are safe if it is the electors who are driving towards aspirational goals.

What has all this got to do with the building industry? After the Paris Conference it has became more widely publicised that New Zealand has been achieving its emission targets by buying carbon–trading credits rather than concentrating on ways to minimise and physically reduce carbon emissions. While in theory this might be a legitimate process, in practice it has many fishhooks. In the mid-2000s I attended a public forum organised by central and local government and business groups to discuss the question of global warming. One presentation was from the ambassador of a European Country who said that they knew the executive in charge of the European carbon-trading scheme, who had said that they were happy to be responsible for the proper management of the process, but would not take responsibility for the effectiveness of the process. On page B5 of The Dominion Post of 26th December 2015 there is an article written by Geoff Simmons, who is an economist with the Morgan Foundation. In the article he presents some of the difficulties of New Zealand's financial approach to carbon emission reduction. Rather than making special pleadings because we have so many belching cows, soon the government is going to have to move to real reductions.

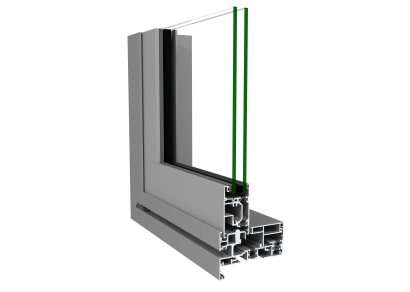

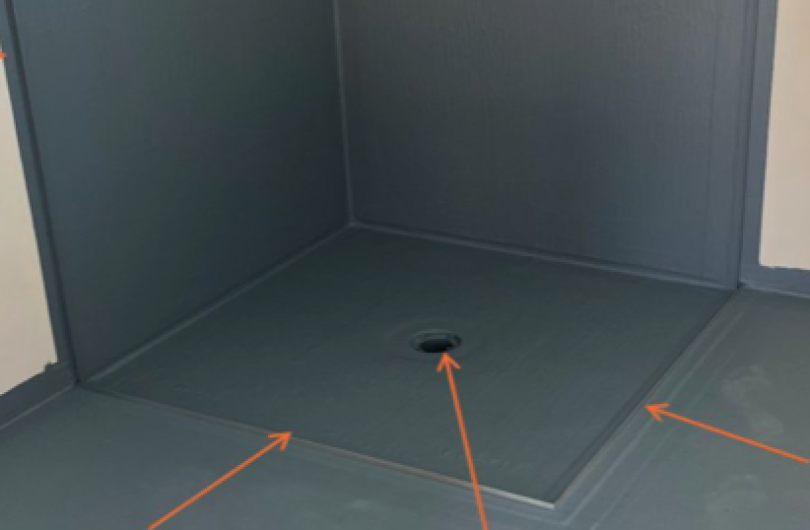

When government decides that it needs to apply genuine physical restraints to the country's carbon emissions, then the building industry is an obvious target, and is a sufficiently large portion of the economy and varied in its aspects, to provide a significant difference. Taking one example, the third edition of NZBC-H1 (Energy Efficiency) was published in 2007 — eight years ago. While it is unlikely that triple glazing will replace double glazed units, and thermally-broken aluminium frames have their limitations, the remainder of NZBC-H1 could be easily tightened so as to make those buildings designed to the current minimum requirements non-compliant. The second–hand house purchaser is becoming more knowledgeable and discerning and therefore in the future the market is likely to consciously discount poor thermal performance to a greater extent than at present. The talk of warrants-of-fitnesses for rental homes is an example of changing attitudes.

The advantage of improving the thermal performance of our building stock — reducing the need for network energy for example — is that the gains continue over the lifetime of the house. As performance improves, the need to objectively determine the gains becomes much more important. Rules-of-thumb do not work due to the multiple interrelated variables affecting building design. Through EcoRate Ltd I have been providing such objective analysis since 2010, and with my practical knowledge as a Registered Architect, I am able to provide comment on projects during the design phases and to undertake thermal performance assessments, all as an independent professional.

Most Popular

Most Popular Popular Products

Popular Products