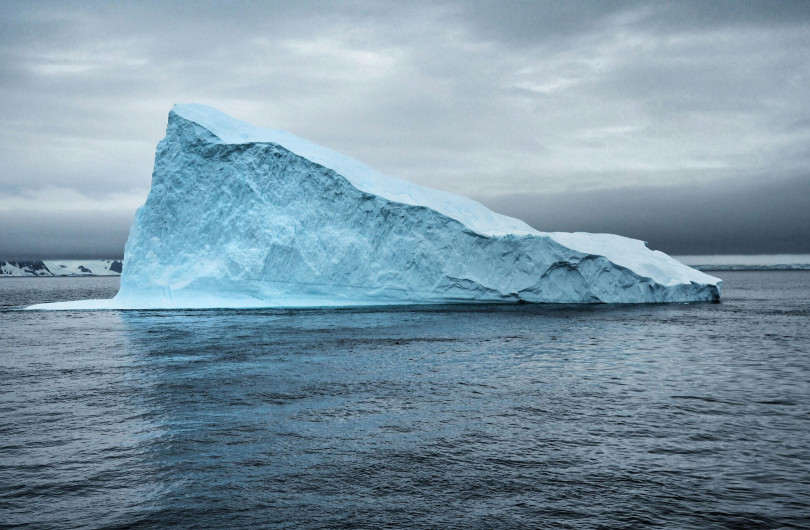

For a moment, let’s assume that every building fit-out in New Zealand is miraculously designed and built to comply with NZS1170.5. Although this would be a vast improvement on the reality*, this means that at best the probability of collapse and failure of these non-structural elements (and therefore the risk to human life) is deemed at an acceptable level. This does not mean that the building interiors are designed to be resilient.

Non-structural elements are a significant percentage of the overall build cost. After damaging earthquakes, they often comprise a large portion of the cost of repair.

The ULS (Ultimate Limit State) design criteria are set to provide the required level of confidence that the life safety objective has been met across all rare events. This doesn’t extend to limiting damage. (SLS2 (Serviceability Limit State) does limit damage for buildings that are required to be functional in the post-earthquake period — fire stations and hospitals for example. When a building is designed to SLS2, there is an expectation that return to a full operational state may take minutes to hours (rather than days). For most commercial buildings, much like the crumple zones in cars, codes and standards are designed to only protect life. Buildings that’s aren’t essential post-disaster are not designed to survive a major event.

In a planet increasingly drowning in waste, can the NZ building industry do better? Should we do better?

Plastic bags are being banned, yet this waste pales in comparison to the amount of construction demolition that has been discarded in landfill since the Canterbury/Seddon/Kaikoura quakes.

Resilience is intricately connected to sustainable design. When it comes to seismic compliance, the concept of resilience makes designers and builders question this short-term cost-centred construction approach. Could resilience, coupled with sustainable design, encourage the construction of higher-quality buildings and infrastructure with a longer-term view? As designers, builders and manufacturers begin to take into account the environmental cost of design decisions, they must extend this thinking to making buildings last after a significant event. Surely this is a better result all-round?

* Kevin O’Conner Associates, Survey of Seismic Restraint Of Non Structural Elements In Existing Commercial Buildings Detailed Seismic Assessment. Report On Stage 2 – Full Study. 2016

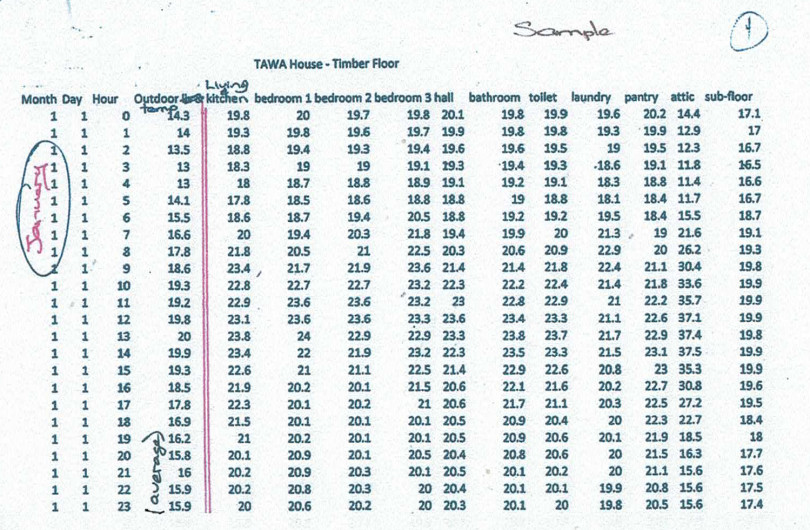

In a study commissioned by MBIE, of 41 larger commercial buildings sampled, 89% of ceilings needed seismic restraint upgrades to comply with the standard, and 85% of interior partitions did. Not only were ceilings unbraced but many plumbing pipes, electrical and data cables, HVAC units and light fittings were supported directly by the ceiling grid or even ceiling tiles. Each of these elements required upgrading.

Case Studies

Case Studies

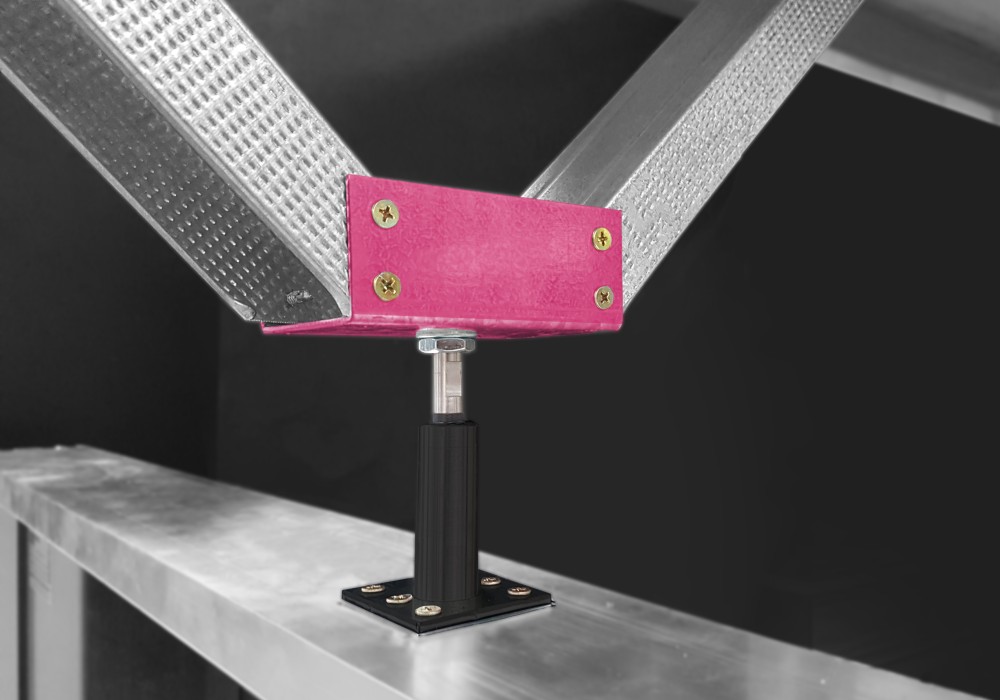

Popular Products from T&R Interior Systems

Popular Products from T&R Interior Systems

Most Popular

Most Popular

Popular Blog Posts

Popular Blog Posts