Housing built before the 2000’s may have been insulated, but generally was not very airtight. There were many places for outside air to enter the internal living space. Since then, there has been a big push to become more energy efficient. This has led to internal living spaces that are designed to be as airtight as possible. The floor, walls, windows and roof are also highly insulated.

Now we keep the external moisture out, but we still produce internal moisture. This can be from cooking, washing, cleaning, plants, pets or just breathing. It is this moisture that causes many issues when we build airtight living spaces.

The problem begins at night when we heat our homes and the outside temperature drops. When warm, moist air meets a cold surface it condenses to surface moisture. This condensation is absorbed into the internal timbers, insulation and linings. Conditions are now perfect for mould to form, which soon begins to decompose any untreated internal products.

This was a contributing factor of the leaky home syndrome from the 1990s to 2015, with some cases still lingering today.

There is a solution.

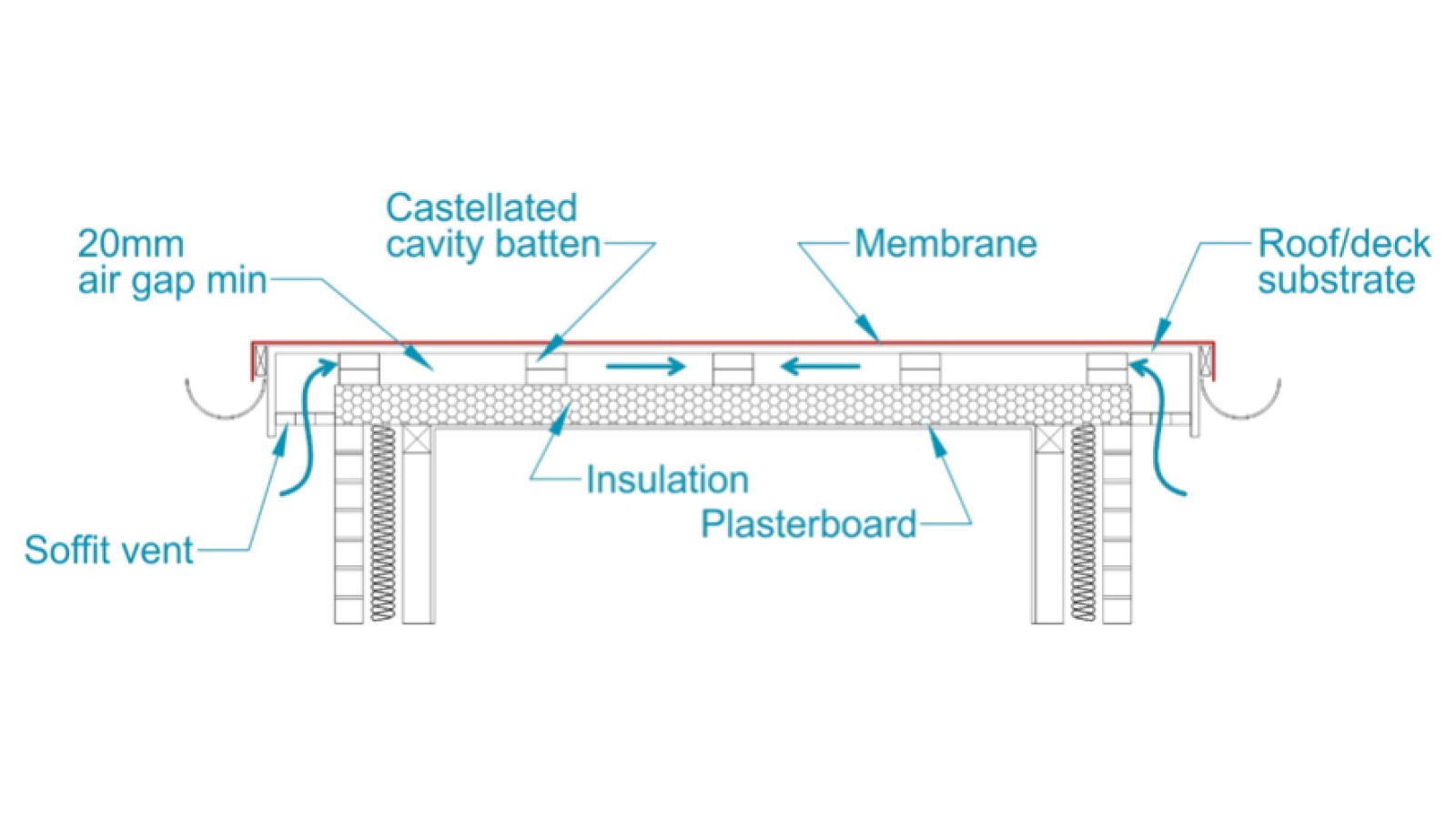

The area between the roof and insulation must have air flow to outside vents. This external air flow between the roof and insulation has two benefits; it allows the warm, moist air to escape while also drying the internal areas of the roof cavity.

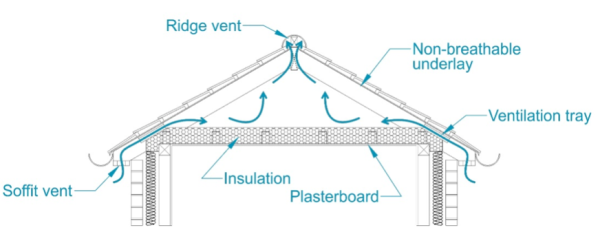

Pitched roofs are easy.

Soffit vents allow air in, and ridge vents allow the air to escape. There is often a large space between the roof and the ceiling.

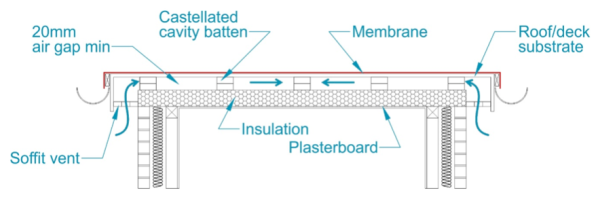

Skillion and flat roofs are more difficult.

The space for air flow here is much smaller. Warm air rises, but in flat roofs with little fall, this thermal cycle can be inhibited, and warm moist air can become trapped. Air pockets with inadequate flow cannot dry out, even as the roof heats up. Wet timber may dry on the surface, but the internal moisture remains. With the onset of night, the warm wet air condenses again, and the cycle continues.

Castellated battens placed atop of the purlins help transfer air to the vents. With a passage to the vents, even without great airflow, the pressure of the warm air will dissipate.

When a cold roof runs hot.

Additionally, in the summer cold roofs can get very hot, especially the dark colours. This heat is transferred into the structure of the building which in turn causes expansion/contraction of the structure and puts more pressure on the membrane where it is joined or fixed to the structure.

Proper venting and airflow as described above alleviates these issues as the heat (and subsequent pressure) is released. The designer must add this into the build.

A question we are often asked is: how many vents are required and where should they be positioned? There are too many variables to give a generic answer so, as always, consult a ventilation expert.

If passive ventilation is too difficult to achieve, mechanical options should be considered.

The WMAI aims to set the benchmark for best industry practice in relation to waterproof membranes.

To view our publications, go to: wmai.org.nz/publications

Most Popular

Most Popular Popular Products

Popular Products